On the night of August 25-26, 2018, a violent altercation occurred at the Chemnitz city festival. Three men are seriously injured by stab wounds, and 35-year-old Daniel H. later succumbs to his injuries in the hospital. The perpetrators are refugees from Syria and Iraq. On the same day, the radical right mobilizes against “foreigner crime” in Chemnitz. Numerous violent attacks on ethnic minorities follow. Several investigations, including for the use of the Hitler salute, are launched. Within a few hours, an individual altercation escalates into a spiral of hate in Chemnitz. Non-white individuals who had nothing to do with the original incident become “vicarious” targets of violence.

The Chemnitz case is an extreme example of local intergroup conflict. Our study investigates whether there is a general link between crimes attributed to out-group suspects and hate crimes against uninvolved out-group members (“vicarious retribution”). While previous research on right-wing violence has primarily focused on structural causes (e.g., local unemployment rates or weak infrastructure), our study emphasizes the short-term, dynamic determinants of hate crimes. We argue that reports about out-group crime can act as triggers for hate crimes against minorities among a small group of radicalized individuals with pre-existing racial stereotypes.

To quantitatively examine the link between crimes attributed to out-group suspects and xenophobic hate crimes, we collected event-level data on both phenomena. First, we coded information on the location and date of over 9,000 hate crimes against refugees between January 2015 and March 2019. Second, we collected a novel data set on immigrant-attributed crime across Germany. German police authorities do not systematically publish event data on crimes committed by foreign suspects. Therefore, our data source is the private website refcrime.info (which has been inaccessible since the end of 2020). This website, associated with the far-right political spectrum, aimed to draw public attention to out-group crime. To this end, it maintained a hand-coded database of all crimes attributed to foreigners or ethnic minorities. The data are based on police press releases and include approximately 17,600 out-group crimes. Our research assistants independently validated the accuracy of this data source. For each crime, information on the location, date, and alleged nationality of the perpetrator was coded. Since we focus on hate crimes against refugees, we specifically focus on crimes attributed to suspects from the main countries of origin of asylum seekers.

We combine these two datasets to statistically estimate the effect of crimes attributed to ethnic out-groups on subsequent hate crimes. For each crime attributed to an out-group member, we examine how many hate crimes against refugees were committed in the same county immediately before and after the event. We find a clear increase in the daily rate of hate crimes against refugees immediately after a crime by a foreign or ethnic minority suspect is reported in social media or local press. Further analyses show that these effects are primarily triggered by violent crimes (such as rape or murder). In line with our theoretical expectations, we do not find any evidence that nonviolent petty crimes or crimes attributed to non-refugee immigrant groups (e.g., Romanians or Bulgarians) lead to a backlash against the local refugee population. We also find suggestive evidence that migrant-attributed crimes are more likely to lead to hate crimes against refugees in areas with deeper support for far-right parties. This suggests that the hate crime dynamics we uncover can be linked to broader local political trends that may legitimize vicarious retribution or create in-group dynamics that foster prejudice and aggression.

Our research makes significant contributions to the literature on hate crimes and attitudes toward out-groups. First, we extend previous findings by showing that vicarious retribution dynamics are not limited to high-profile national events but are a frequent occurrence at the local level. While previous studies focused on the surge in hate crimes after nationally or internationally salient events, our work highlights that localized crime events reported in the local news media also lead to increased hate crimes against refugees. This indicates that everyday local events can drive intergroup conflict, making the phenomenon more pervasive than previously thought. Second, our empirical strategy offers new insights into the short-term nature of vicarious retribution. We find that hate crimes spike immediately following a crime attributed to an out-group and return to baseline levels within a few days. This rapid decline suggests that these hate crimes are driven by emotional reactions rather than sustained changes in attitudes. Finally, our study uncovers the contextual factors that influence vicarious retribution dynamics. Contrary to prior research indicating that hate crimes increase in areas with low levels of pre-existing anti-immigration sentiment following high-profile events, we find that at the local level, such dynamics are more pronounced in regions with strong far-right support. This suggests that local political climates and recent demographic changes play critical roles in the occurrence of hate crimes following immigrant-attributed crimes.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Out-Group Threat and Xenophobic Hate Crimes: Evidence of Local Intergroup Conflict Dynamics between Immigrants and Natives” by Sascha Riaz, Daniel Bischof, and Markus Wagner

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

Note

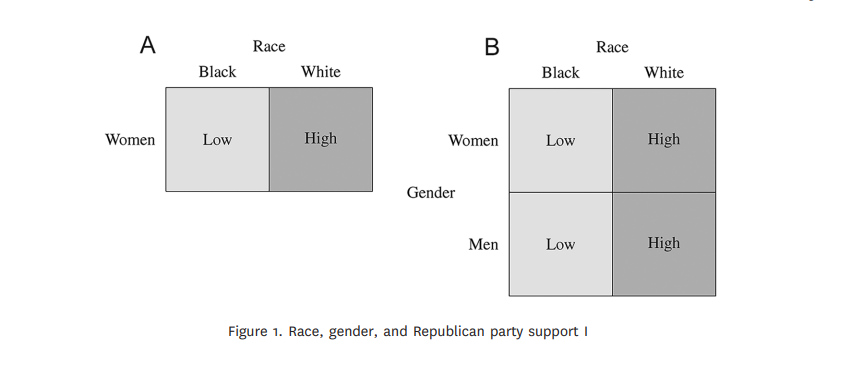

Fig. 1: Transformation of event-level data to the data we use for the RDIT design. We use the example of a stabbing that occurred in the East German city ofChemnitz on August 26, 2018. The running variable is the time in days relative to an immigrant-attributed crime event. We consider the two-week periodbefore and after each crime event. For this illustration, we discard the possibility of partial overlap between events.

About the Authors

Sascha Riaz is a Postdoctoral Prize Research Fellow in Politics at Nuffield College, University of Oxford. His research centers on political behavior in industrialized democracies, with a focus on immigration, xenophobia, and political violence. Personal website: https://saschariaz.com/

Daniel Bischof is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Münster (Germany) as well as Associate Professor of Political Science at Aarhus University (Denmark). He studies some of the key challenges contemporary democracies are facing such as the rise of extremism, its societal consequences, remedies to mitigate extremism, and the erosion of social norms more generally. His research is published in the American Journal of Political Science, the American Political Science Review, the British Journal of Political Science, and the Journal of Politics among others. Personal website: https://www.danbischof.com/

Markus Wagner is a Professor in the Department of Government, University of Vienna, Austria. He studies the role of issues, ideologies and identities in party competition and electoral behavior. Personal website: https://www.wagnermarkus.net/