After the 2020 killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, protests against police brutality swept the country. Community-led movements called for policy changes ranging from defunding the police to ending chokeholds to investing in new social programs, and hundreds of cities and law enforcement departments across dozens of states pledged reform.

Amid these debates, one proposal that gained traction was the idea of residency requirements, or mandating that police officers reside in the communities where they work. Supporters of these laws tout their ability to bolster the local tax base, increase the diversity of municipal employees, and foster deeper and richer ties between officers and their communities. But opponents of these rules (including police unions) have argued that residency requirements limit the talent pool for officer recruitment and can create safety issues for officers during periods of increased tension between communities and law enforcement.

While places like Chicago and Buffalo have maintained police residency laws for decades, cities including Rochester, Milwaukee, and Baltimore are currently considering enacting new residency guidelines. Still other high-profile cities have just recently had their residency rules overturned by their state legislatures—including St. Louis in 2020.

Do Residency Rules Matter?

Using an original survey and archival sources, we collected original data on the history of residency requirements for every city policy agency with at least 100 officers over the past 30 years, covering nearly 800 cities in total. We then test two key policy claims about whether residency rules (1) promote police force diversity and (2) improve police-civilian contact.

Simply comparing cities with residency rules to cities without these requirements would likely generate misleading conclusions. For example, cities that have residency rules to be larger and be home to more racially diverse residents. To address this challenge, we exploit the fact that a growing number of cities have dropped their residency rules in recent years, which allows us to compare the same cities over time. In some cases, the change was initiated locally via city council ordinance or internal department policy. Other times, state legislatures forced cities to abandon their residency requirements, which was the case in Michigan in 1999 and Ohio in 2006.

Residency Rules Increase Police Diversity But Fail to Reduce Civilian Fatalities

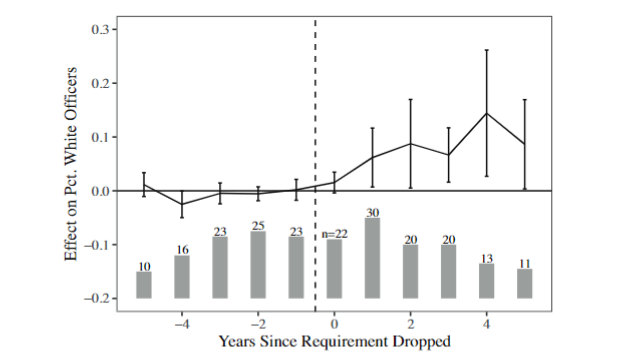

One of the key arguments in favor of residency requirements is that they limit white officers from living in the suburbs while working within an inner city. Using data from the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics Survey, we find that once a city drops its residency requirement, the percentage of white police officers increases in subsequent years. This is true whether a city initiates the residency change locally or is forced to do so by state law.

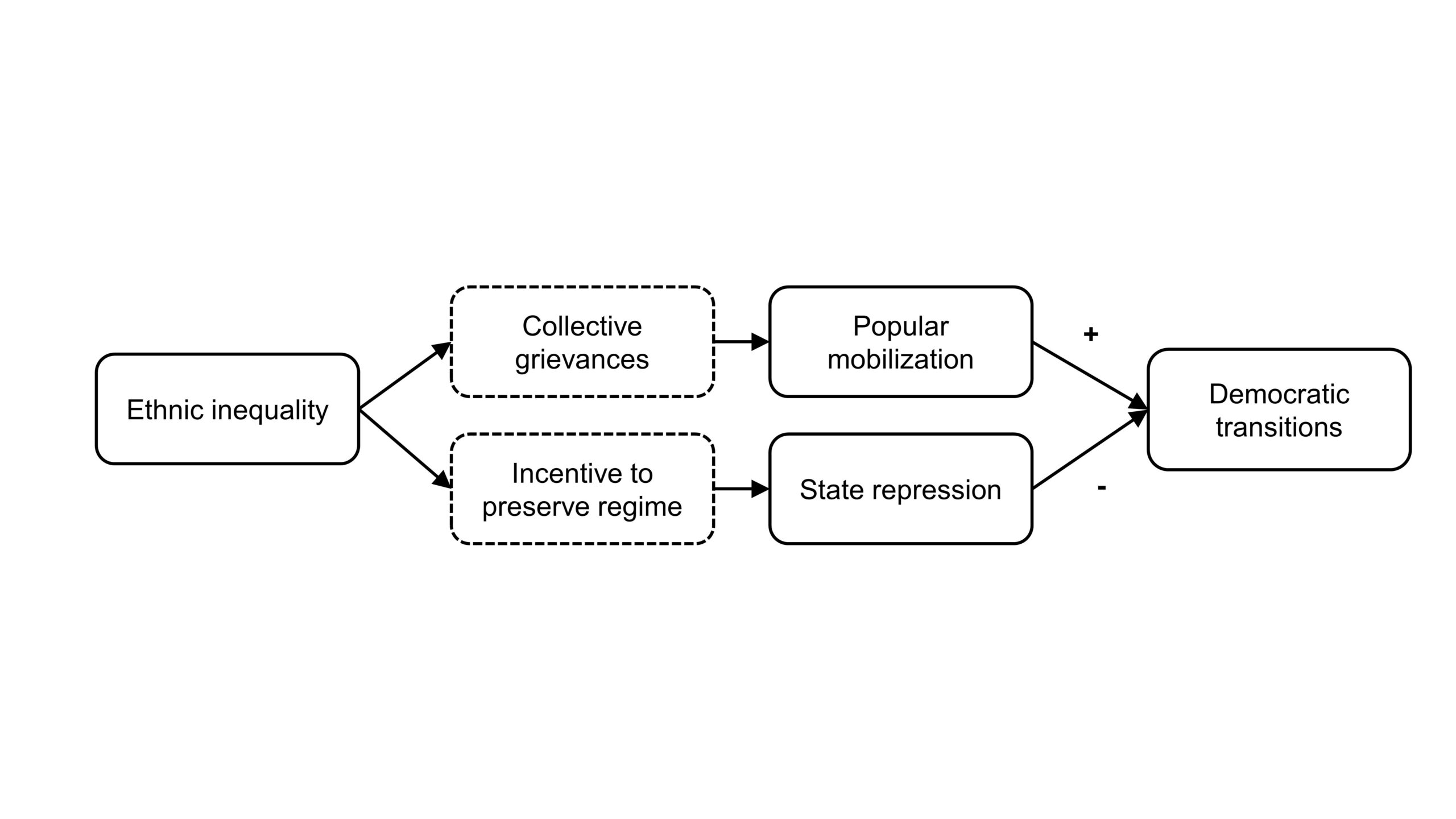

The fact that police departments become whiter after dropping their residency laws—especially in diverse cities—might mean that police-civilian relations subsequently deteriorate. However, some research finds little change to policing performance after departments hire more officers of color. If relaxing these laws bolsters the quality of the talent pool or enhances officer morale, it’s possible that police-community relations might actually improve in the absence of residency requirements.

To study how residency rules affect police-civilian contact, we focus on the annual number of civilian fatalities that occur during interactions with police. These data come from fatalencounters.org, a comprehensive open-source system that tracks police-related deaths going back to the year 2000. Perhaps surprisingly, we find that civilian deaths actually decrease after cities drop their requirements. However, this effect is driven by cities that voluntarily drop their residency rules, rather than being compelled to do so by state mandate.

Are Residency Rules A Substitute for Real Reform?

Why would cities reduce the rate of fatal encounters when they drop their residency requirements? One possibility is that these rules restrict the labor market and make it challenging for agencies to hire qualified applicants. Sure enough, we find that agencies that drop their residency rules internally subsequently grow in size. The data are consistent with the idea that cities might drop their residency rules when they are struggling to recruit enough applicants. Relaxing the residency requirement allows them to hire more officers and operate at full capacity, which could improve fatal encounters if officers were previously overworked.

Another possibility is that when a city chooses to drop its residency requirement, it does so while adopting other, higher-impact reforms with the goal of improving police performance. We uncover some evidence consistent with this story. When cities drop their residency rules, they are more likely to subsequently create civilian complaint boards and to administer resident satisfaction surveys. This analysis suggests that residency requirements may simply reflect blunt policies that are substituting for more meaningful reform.

A growing body of evidence-based research demonstrates that certain public safety reforms can effectively improve police department performance. These include clear bureaucratic guidelines for monitoring civilian stops, training in procedural justice, and the use of body cameras. However, when it comes to residency requirements, both supporters and opponents of these laws tend to make sweeping claims that simply aren’t supported by evidence. Ultimately, our results are consistent with what many community reform groups have recently argued: residency laws do not appear to improve police-community relationships and are likely not a particularly fruitful path to reform in the absence of other structural changes.

Notes

Fig. 1: Event Study: Police Force Diversity. Figure generated via fect in R. Histogram shows number of treated units in each period.

This blog piece is based on the forthcoming Journal of Politics article “Residency Blues: The Unintended Consequences of Police Residency Requirements” by Julia Payson and Srinivas Parinandi

The empirical analysis has been successfully replicated by the JOP and the replication files are available in the JOP Dataverse

About the Authors

Julia Payson is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on representation, political institutions, and public policy in state and local governments in the U.S. Personal website.

Srinivas (“Chinnu”) Parinandi is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder and Fellow at the Renewable and Sustainable Energy Institute. His research focuses on how the design of institutions and rules influences policy outcomes in American politics. Personal website.