Americans have little trust in political institutions with one notable exception: the U.S. armed forces. In 2019, 73 percent of Americans reported confidence in the U.S. military compared to only 38 percent for the Supreme Court and 11 percent for Congress. This is no secret to politicians. Civilian leaders often publicly highlight the input and expertise of their military advisors to help build support for their actions. Our article, “You and Whose Army? How Civilian Leaders Leverage the Military’s Prestige to Shape Public Opinion” asks: How does a popular military change what civilian leaders can get away with in their foreign policy decisions?

We are not the first to raise concerns about how an increasingly popular military can influence democratic norms and institutions, though we explore the issue along new dimensions. Other scholars raise concerns that the military’s popularity gives the armed forces undue political influence, tipping the balance of decision-making towards unelected military officials. We identify a new, paradoxical dynamic that threatens democratic norms, the reputation of the armed forces, and national security: the military’s popularity empowers civilian leaders to take foreign policy risks.

At the beginning of an international crisis, leaders seek to bolster their public support. With the public on their side, leaders reduce opposition from other political elites, better navigate domestic institutions, and protect their reelection prospects. A savvy communications team will help leaders reap these benefits by emphasizing the parts of a policy decision that appeal to the public while guarding against factors that create skepticism or opposition.

The backing of any expert can increase support, but references to advice from military officials is especially coveted. We argue that presidents take care to identify advisors within the military who share their views and to amplify these voices when selling their decisions to the public. We expect that this is especially true when foreign policy decisions carry high political risks. When presidents mention military advice, we expect that they will receive greater support for decisions to use (or not to use) military force, and that they will be punished less for failure.

This argument creates expectations at two levels: 1) for how the public responds when leaders mention military advice, and 2) for when leaders talk about military advisors. To evaluate public expectations, we use a national survey experiment that varies whether a president references civilian or military advice. We test speech-level expectations by analyzing presidents’ national addresses about military interventions abroad.

Takeaway One: Referencing military advice empowers civilian leaders, even when they fail

Participants in the survey experiment read a hypothetical president’s statement about a possible counterterrorism raid. In this statement, the president references his National Security Advisor who is randomly either a military general or a civilian. The president says his decision is based on the advisor’s recommendation. The conflict then has one of the following outcomes: the US engages in a military raid, the US stays out of the conflict, the US engages and the raid succeeds, or the US engages and the raid fails.

In almost every scenario, significantly more people approved of the president when he referenced military advice compared to when he referenced a civilian advisor. Only when the raid is a clear success is the public indifferent as to which type of advisor is consulted. This means that leaders looking to increase public support at the beginning of an intervention benefit from mentioning military advice. Critically, references to military advisors lower the political costs presidents pay for taking foreign policy risks—staying out of a conflict after raising its public profile or engaging in military action that fails.

Takeaway Two: Benefits to the Leader Create Risks for the Military

For people who read that the counterterrorism raid succeeded or failed, we also asked whether they held the president, the advisor, or both responsible for how the intervention turned out. People were more likely to give military advisors credit for success compared to the president. Surprisingly, we find an even stronger gap in responsibility when the mission fails. More individuals who read about military advice blamed the advisors for the failure (20.4% vs. 13.3%) and fewer laid blame at the feet of the president (25.8% vs. 38.6%). Because military advisors are more likely to be blamed for foreign policy failures, the costs of politicizing military advice appear to fall more at the feet of military elites than on the civilian leaders politicizing their advice. In the long-run, leaders’ efforts to use a popular military to their political advantage risk undermining the reputation of the armed forces.

Takeaway Three: Leaders actually do talk about military elites in a way that reaps these benefits.

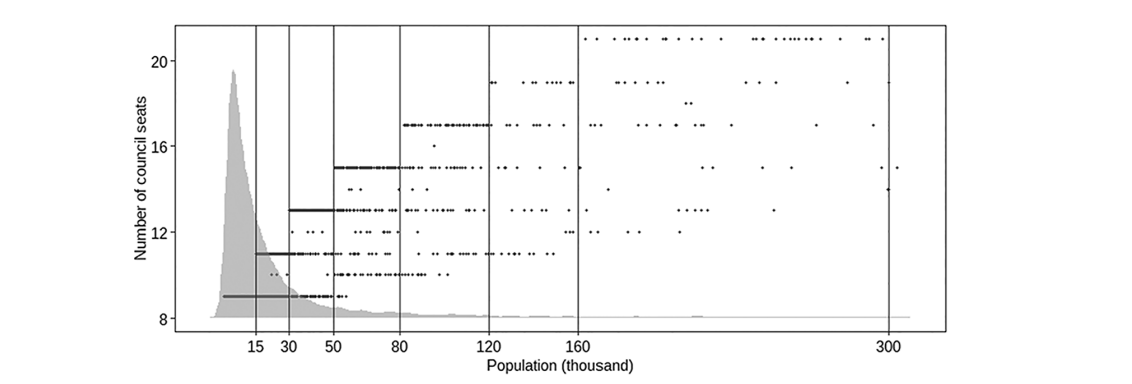

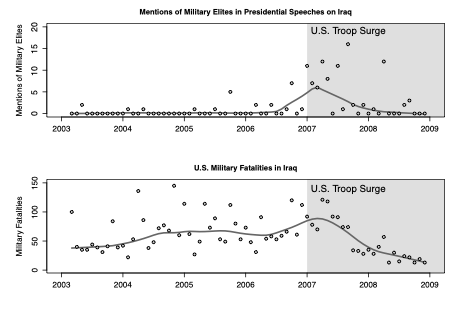

The survey experiments show that leaders who reference military advisors can expect a boost in public support, but do presidents actually talk in a way that allows them to receive these benefits? We answered this question by examining 798 presidential addresses about military interventions, 1990-2013. We find convincing evidence that leaders are strategic and intentional in how they reference military advice. First, leaders are more likely to refer to military elites in speeches that otherwise have a negative rhetorical tone, which we believe is a sign that the leader is conveying the political costs or risks associated with military operations. Second, we focus more closely on George W. Bush’s speeches before and after the 2007 troop surge in Iraq—a moment when the risks of political backlash and failure were particularly high. Bush’s references to military advice increased with military casualties in the uncertain early stages of the surge and declined as its effectiveness became more apparent.

In brief: the armed forces’ popularity incentivizes leaders to draw the military further into politics to bolster public support and minimize the electoral risks associated with foreign policy decisions.

This blog piece is based on the article “You and Whose Army? How Civilian Leaders Leverage the Military’s Prestige to Shape Public Opinion” by Michael R. Kenwick and Sarah Maxey, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 4.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Michael Kenwick is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at Rutgers University. His research is in international relations with emphases in conflict processes, civil-military relations, and border politics. You can find more information on his research here and follow him on Twitter: @MichaelKenwick

Sarah Maxey is an Assistant Professor in the Political Science Department at Loyola University Chicago. Her research examines public opinion towards the use of force and how democratic institutions shape foreign policy. You can find more information on her research here and follow her on Twitter: @smaxey265