“A lot done. More to do.” The Irish party Fianna Fáil used this slogan as their central message of the 2002 election campaign. The party had been in government during the so-called “Celtic Tiger” boom, a period of rapid economic development from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s. “A lot done. More to do” aimed to remind voters of the party’s achievements while also outlining policy proposals and goals for the future. Such an electoral strategy makes sense, given that evidence from psychology shows that humans think about the past and present when making decisions or predicting the future.

Voting at elections also involves a time perspective. Citizens consider retrospective and prospective factors when casting their ballot for parties or candidates. Retrospective voting implies that voters choose between parties based on past performance, the status quo, or economic developments. Prospective voting entails comparing the promises made by parties for the upcoming term.

Political parties and politicians should strategically emphasize the past, present, and future. However, empirical and theoretical studies on party communication directly or indirectly assume that party communication is prospective by describing future policy goals. We lack comparative evidence on the temporal focus of party communication.

I address two questions in a new paper published in the Journal of Politics. First, to what degree do parties emphasize the past, present, and future? Second, do incumbents and opposition parties apply different levels of emotive rhetoric in retrospective and prospective statements?

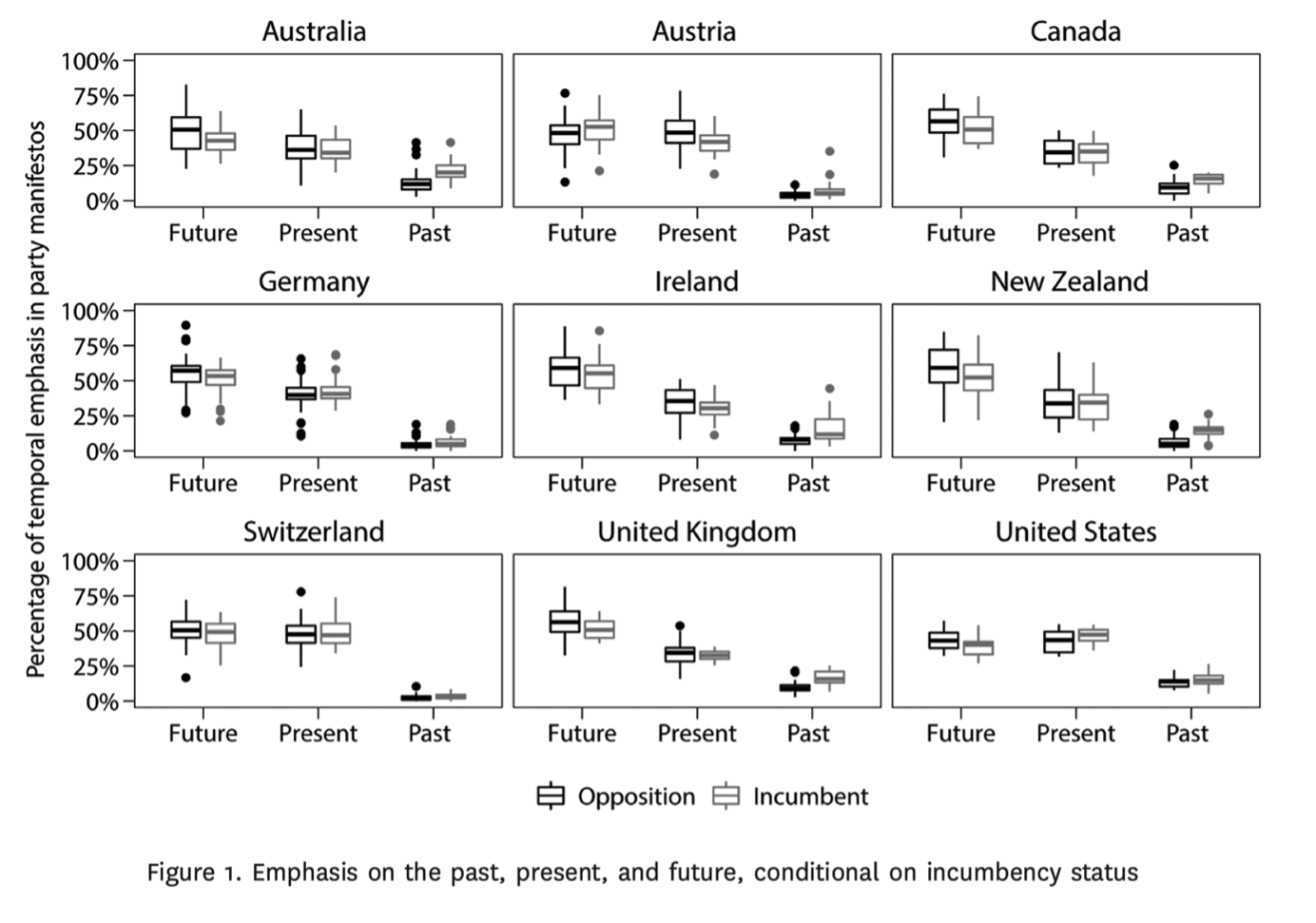

I uncover the temporal focus of over 380,000 sentences from 621 party manifestos, drafted before 150 elections across nine countries between 1949 and 2017. Based on thousands of hand-coded English and German sentences, I train and validate a supervised machine learning classifier to identify whether a sentence addresses the past, present, or future. The analysis reveals that campaign communication is not only prospective. Only around half of the average party manifesto is devoted to the future. Around 10 per cent of all sentences relate to the past, while 40 per cent address the present. I also find that incumbent parties tend to focus more on the past than opposition parties (see plot below). Parties clearly communicate policy goals, achievements, and criticism in their manifestos.

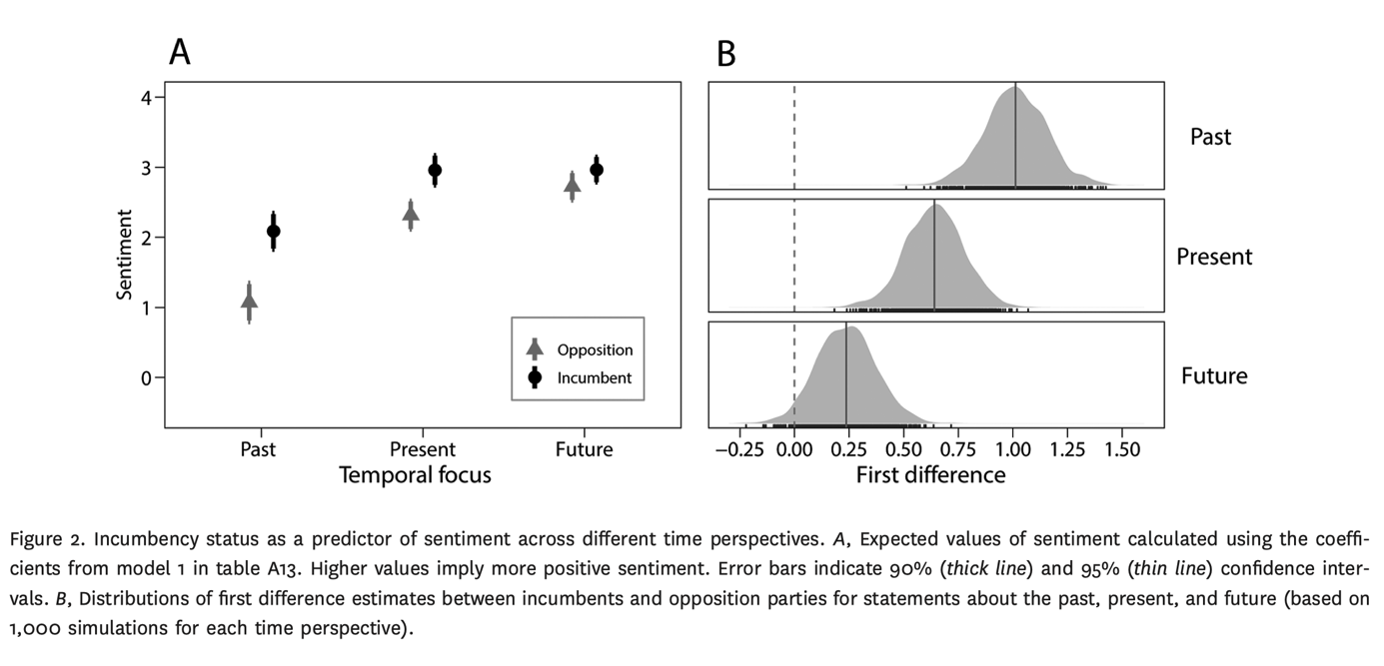

Having shown that party communication is not only prospective, I extend recent studies on emotive rhetoric. Kosmidis et al. (2019) and Crabtree et al. (2020) show that incumbent parties express more positive sentiment than opposition parties. I expect that the temporal focus conditions the differences based on incumbency status. In statements on the past, the opposition should blame and attack the government, while the government praises achievements or the current situation. I do not expect large differences between incumbents and opposition parties in statements on the future. Describing the future in a very negative way may not be a vote-winning strategy for most parties.

I follow Crabtree et al. (2020) and measure sentence-level sentiment using a dictionary approach. The results from various regression models provide robust support for this expectation. The figure below reports expected values and first differences between opposition parties and incumbents. Opposition parties express much more negative sentiment than incumbents in their assessment of the past. This difference becomes smaller in discussions of the current situation and almost disappears in statements on the future. Focusing on the temporal dimension of communication reveals essential differences between parties’ campaign strategies.

I hope the results presented in this paper encourages future research to pay more attention to the temporal dimension of political communication. Future work could address several open questions by applying a similar empirical approach. For example, researchers could study whether incumbents frame the past and present more or less positively when public support for the party is low or the economy performs poorly. In addition, scholars could measure nostalgic appeals in campaign communication, assess whether certain policy areas are avoided in retrospective or prospective communication, and test whether latent party positions differ in retrospective and prospective manifesto sections. Answers to these questions will further improve our understanding of the temporal rhetorical dimension of party competition.

This blog piece is based on the article “The Temporal Focus of Campaign Communication”, published in the current issue of the JOP, Volume 84, Number 1.

The replication materials are available at The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the author

Stefan Müller is an Assistant Professor and Ad Astra Fellow in the School of Politics and International Relations at University College Dublin. His research focuses on political representation, party competition, political communication, public opinion, quantitative text analysis, and the application of computer vision techniques. You can find further information regarding his research here and can follow him on Twitter.