On January 28, 2015, Brock Turner, a Stanford student athlete, sexually assaulted Chanel Miller, a visiting student. (Miller has expressed a preference not to remain anonymous.) Turner was arrested, and five days later, indicted on two counts of rape, two felony sexual assault counts, and one attempted rape count. In March of 2016, he was convicted on the sexual assault and attempted rape charges.

Turner faced a maximum sentence of 14 years for these convictions, but on June 2, 2016, the presiding judge, Aaron Persky, sentenced him to just six months in prison and three months’ probation. The lenient sentence made national headlines owing to Miller’s wrenching impact statement and sparked widespread outrage and condemnation. Several days later, on June 6, a Stanford Law School professor announced the formation of a committee and began collecting signatures to recall Persky. According to journalistic sources, the committee raised more than a million dollars for the recall effort, and the voters ultimately recalled Persky in June of 2018.

While the leniency of Persky’s sentence was widely condemned, a host of critics, including law professors, judges, public defenders, and elected officials, denounced the recall effort. They did so not because they felt Persky’s sentence of Turner was appropriate, but rather because they believed the recall itself — or, more accurately, the recall *campaign* and the fear it might induce in *other judges* — might have pernicious effects on the administration of criminal justice.

Specifically, these critics worried that the fear the campaign would induce would lead judges to become more severe in their sentencing behavior. (As has been exhaustively documented elsewhere, the punitiveness of judges affects not just the sentences imposed following guilty trial verdicts, but also those arrived at via plea bargaining.) And importantly, the defendants most likely to bear the brunt of this increase in sentencing severity wouldn’t be affluent white Stanford students accused of sexual assault, but the broader population of criminal defendants in California courts, which is, of course, disproportionately composed of defendants of color.

In other words, critics of the recall predicted that even if Persky himself deserved sanction, the effort to punish him would inflict significant collateral damage on a vulnerable population.

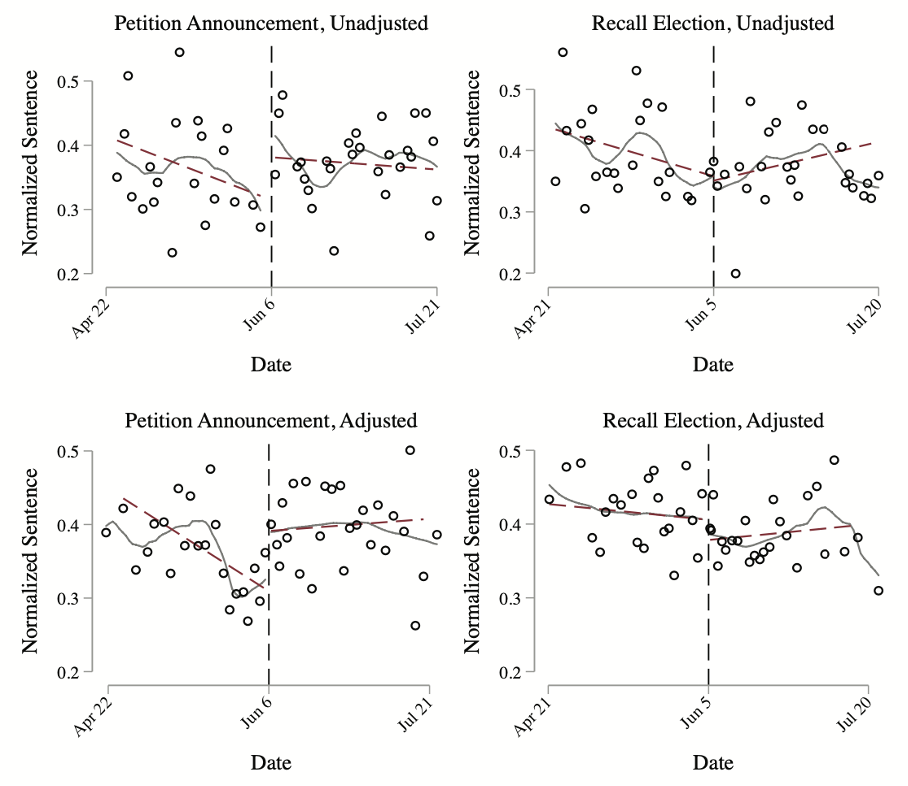

Our paper, “Incentive Effects of Recall Elections: Evidence from Criminal Sentencing in California Courts,” evaluates this prediction empirically, using disposition data from six California counties. Our main approach is regression discontinuity in time (RDiT), and we look for discontinuous increases in sentences in the immediate aftermath of the petition announcement and the recall itself. Several sets of findings emerge:

- There was a substantively large, discontinuous jump in criminal sentence severity immediately following the June 6, 2016 petition announcement. We document this increase using various measures, but using our preferred measure (essentially the actual sentence divided by the maximum possible sentence), the data suggest an instantaneous increase of around 30% following the petition announcement. We show that this increase was unlikely to have been a consequence of the lenient Turner sentence itself, an adjacent primary election, or strategic adjustment by opportunistic prosecutors.

Moreover, we observe no corresponding effect for the recall election itself. This null result, coupled with the strong result for the announcement, suggests that by the time of the election, Persky’s anticipated defeat was already “priced in” to the decisions of other judges. It also suggests the importance of the media: we conducted a supplementary analysis of media coverage of the two events. Unsurprisingly, the announcement received far more attention than Persky’s defeat, which garnered barely any coverage at all.

- The effect of the announcement was most pronounced for non-sexual violent crimes, next for nonviolent crimes, and least for sex crimes. To be clear: there are very few sex crimes in our dataset, which may account for the null finding for those convictions. But at the very least, the findings suggest the incentive effects of the recall spilled over to defendants convicted of very different crimes from those for which Persky had sentenced Turner so leniently.

- The effect of the announcements neither mitigated pre-existing racial disparities in sentencing nor exacerbated them. Specifically, the largest jump in sentence severity following the petition announcement was for White defendants. However, this increase did not mitigate the already substantial pre-announcement racial disparities in sentence length.

Note that some critics of the recall campaign argued that the over-representation of Black and Hispanic defendants meant that even a race-neutral increase in overall severity might place a disproportionate burden on minority communities. Our findings are consistent with this interpretation.

What is the broader import of our findings? First, the results suggest that one cannot separate the selection effects of a recall campaign (aimed at removing a specific officeholder) from its broader incentive effects. Recall campaigns do not exist in a vacuum, and their occurrence may alter the expectations of other officeholders in a way not anticipated by their supporters. Second, our findings contribute to a broader literature on the electoral incentives of public officials. We find evidence that the threat of recall does affect the behavior of those officials, a relationship that is generally difficult to establish empirically. Finally, our findings provide a roadmap for studying the effects of unusual — and perhaps insufficiently well-understood — electoral institutions.

This blog piece is based on the article “Incentive Effects of Recall Elections: Evidence from Criminal Sentencing in California Courts” by Sanford C. Gordon and Sidak Yntiso, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, Volume 84, Issue 4.

The empirical analysis of this article has been successfully replicated by the JOP. Data and supporting materials necessary to reproduce the numerical results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse.

About the authors

Sanford C. Gordon is Professor of Politics at New York University. His research interests include research on the political economy of domestic governing institutions, with specific substantive applications in electoral accountability, law and public policy, interest group politics, bureaucratic and administrative politics, regulation, constitutional design, and political legitimacy. You can find further information about his research here and follow him on Twitter @sanford_gordon.

Sidak Yntiso is a Ph.D. candidate in the Wilf Family Department of Politics at New York University. He conducts research on the role of political institutions in shaping persistent inequities, focusing on racial disparities in criminal justice and electoral representation. His work has been published or is forthcoming at the Journal of Politics, the Journal of Legal Studies, Political Analysis, and other journals. You can find more about his research here and follow him on Twitter @SYntiso.