Social unrest often begins suddenly and spreads quickly.

How does social unrest diffuse? This is the question we address in our forthcoming article. Our starting point is that riots diffuse when information about them spreads to new locations and reaches new individuals. This raises a number of important research questions: what are the networks that link these individuals together and allow the information to travel? Is the information about repression by the authorities? And who responds to this information?

Following in the research tradition of historical political economy, we address these questions by collecting detailed historical data that we analyze using a carefully laid out identification strategy. Our work in this project also draws on network analysis and spatial econometrics.

The Swing riots

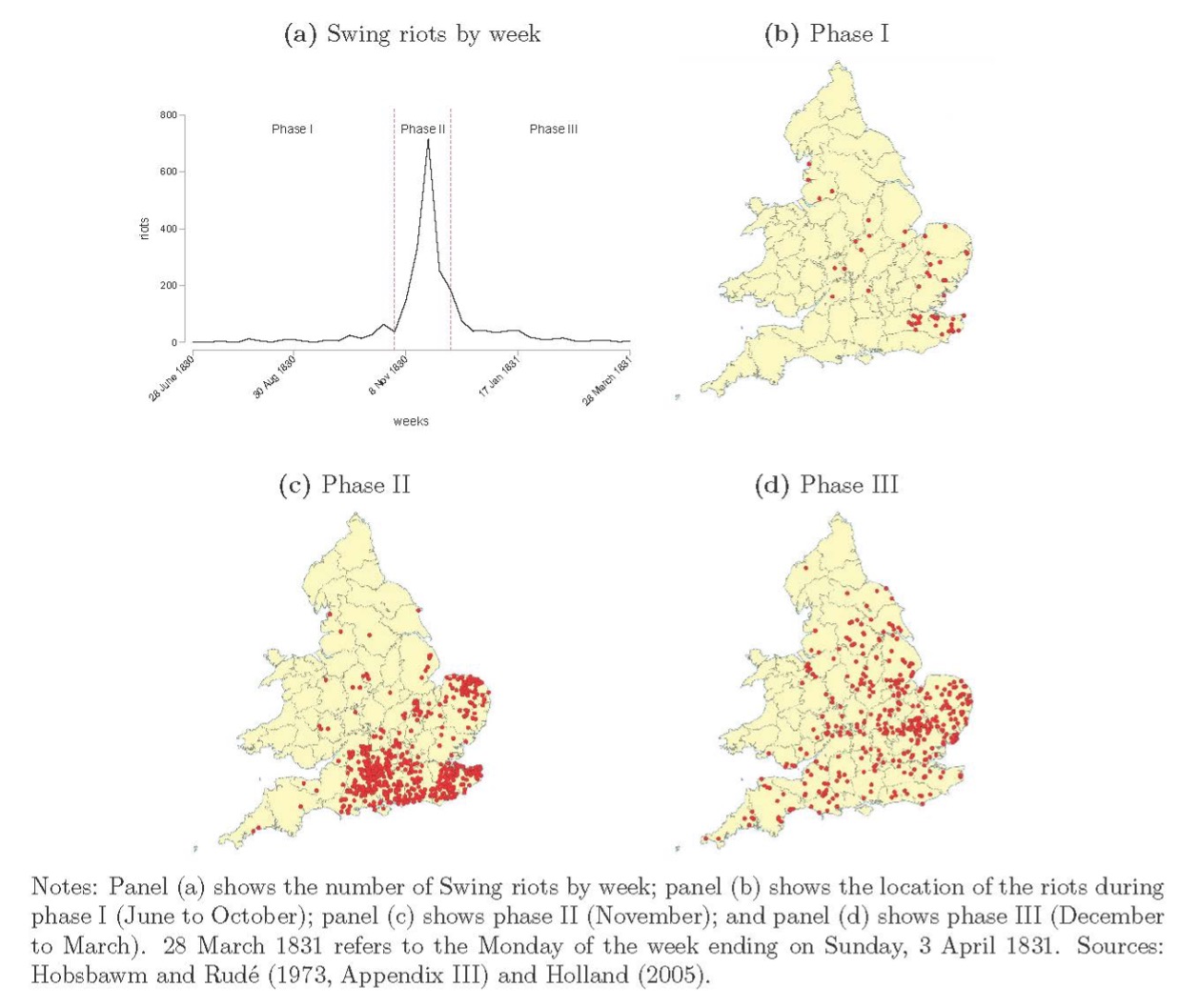

Our article focuses on the diffusion of the Swing riots, a wave of unrest that swept through rural England in the winter of 1830-31. We have data on every English parish (there were over 10,000 of them) and the location, date and type of incident for just under 3,000 Swing riot-related incidents. Although historically known as riots, these incidents were quite varied in nature and are best thought of as belonging to a “repertoire of contention”.

But why look at the Swing riots? Our reasons coincide with two of the key arguments often given to motivate work in historical political economy: the Swing riots represent a good setting in which to consider more general theoretical propositions, and they are an interesting historical case in their own right.

The main challenge in identifying diffusion empirically is what Buhaug and Gleditsch refer to as the reverse Galton problem: what appears to be diffusion may instead be the result of unit attributes that are spatially clustered. The Swing riots offer a way around this econometric problem: they happened in slow motion, with the riots spreading over the course of a few weeks so that the diffusion is observable, yet they spread fast enough for everything else to remain largely unchanged during the period of diffusion. Econometrically, this means that the only variable that changes during these few weeks is the number of riots in the neighborhood of a location (i.e. the spatial lag), allowing us to use a fixed effects specification to estimate diffusion.

Our second reason for studying the Swing riots is that they were an important historical event: Aidt and Franck have recently shown that these riots put pressure on parliament to vote in favor of the Great Reform Act of 1832, the first of the 19th century franchise extensions in Britain. And because of this, the Swing riots were the topic of Hobsbawm and Rudé’s classic social history book on civil unrest.

Networks of diffusion

We study how the Swing riots spread across England. Unlike recent work that has looked at the protest decision of educated individuals, the Swing riots were a movement of poor and uneducated farm workers. How did they learn about the riots? The historical context, coupled with the poverty and relative isolation of the participants, means that information could only travel in a small number of ways.

We find that local face-to-face interactions drove much of the diffusion. Some of these interactions appear to have occurred during the many fairs that took place in the English countryside. We also look at the role of the transport network and of local newspapers, but neither affected diffusion. This is perhaps not surprising given that this was a movement of mostly illiterate farm workers who rarely traveled far from home.

Was the information about repression?

Could it be that the information that traveled between locations was about the response of the authorities? In particular, did information about repression (or the absence of repression) play a role in the diffusion of the riots? We find that repression reduced future rioting in the locations where the repression happened, but it did not reduce rioting in other locations. In short, the diffusion of the riots does not appear to have been a result of the spread of information about the absence of repression.

Organized or spontaneous?

While some studies have shown that riots can be organized by political leaders (Wilkinson), others assume that riots are spontaneous and spread without the need for organizers (Epstein). Were the Swing riots organized, or did they happen spontaneously? It is difficult to observe local organization, but for 1830s England we have a good proxy: at the time, local organizations were active in sending petitions to parliament asking, for example, for slavery to be abolished or for Catholics to be given full rights. Using the number of petitions sent from a location as a measure of that area’s political organization, we find that local organizers played an important part in the diffusion of the Swing riots.

The Swing riots were of great significance in British history, but they also represent an excellent setting in which to test general theories and hypotheses about the diffusion of social unrest.

This blog piece is based on the article “The Social Dynamics of Collective Action: Evidence from the Diffusion of the Swing Riots, 1830–1831” by Toke Aidt, Gabriel Leon-Ablan, and Max Satchell, in the current issue of the JOP.

The empirical analysis of this study has been successfully replicated by the Journal of Politics. Data replication materials are available at The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the authors

Toke Aidt is a University Reader in Economics at the Faculty of Economics, University of Cambridge and a fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is a past-president of the European Public Choice Society. His research focuses on social conflict and democratization, democratization and redistribution, foreign influence and corruption. You can find further information regarding his research here.

Gabriel Leon-Ablan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Economy at King’s College London. He studies collective action, social order and political development, with a recent focus on how non-democratic regimes stay in power and what can be done to challenge them. You can find further information regarding his research here and follow him on Twitter: @gabrieljleon

Max Satchell is a Research Associate in the Department of Geography, University of Cambridge. He works on the occupational structure of England in 1379-1881, transport networks c.1360-1947, and various aspects of disease in the past. You can find further information regarding his research here.