Today, the US media market is both “high choice” and fragmented. This situation stands in stark contrast to the information environment of the 1970s and 1980s, when the three major television networks (i.e., ABC, CBS, NBC) and the similarity of their news programming created a true “information commons” shared by virtually all Americans. Today’s media environment — characterized by the availability of numerous partisan news providers (Fox News, Huffington Post, etc.) — has been blamed for any number of dire outcomes including “filter bubbles” and intensified political polarization.

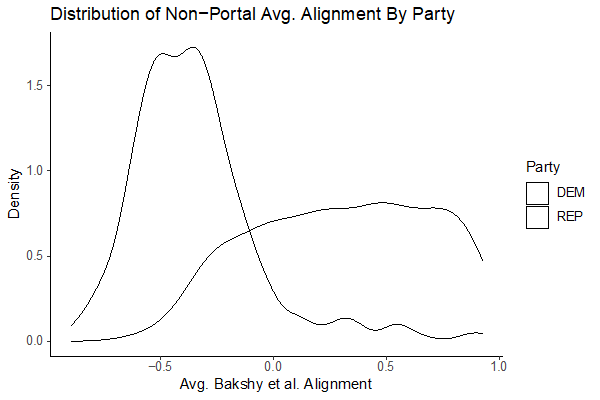

Given this backdrop, it is perhaps surprising that previous studies of online news consumption find so few individuals trapped in filter bubbles or otherwise heavily biased media diets. Quite remarkably, these earlier studies implied that most Republicans preferred neutral sources to Fox-News-style online news, and, similarly, most Democrats preferred neutral sources to MSNBC-style online news.

Our forthcoming article in the Journal of Politics shows that online news consumption was far more partisan in 2016 than predicted by earlier, more-optimistic studies. We obtained daily web browsing data (with consent) from a representative sample of approximately one thousand US adults during the 2016 general election (Aug. 1 through Nov. 7). For ninety-nine days, we observed how many and which online news webpages each Democrat, Republican, and non-partisan in our sample visited.

Our studies took place during one of the most polarized and contentious presidential elections in living memory, and our data reflect this. In our article, we present two main studies that show online news consumption is more partisan and polarized than described in previous studies.

In our first study, we show that, over the course of the 2016 election, both Democrats and Republicans got the vast majority of their news from two categories of news sources. The first category is the partisan news sources often associated with filter bubbles in 2016: Fox News, Breitbart, etc. for Republicans and Huffington Post, The New York Times, etc. for Democrats. There is clear polarization in this category: Democrats almost never visited news sources from this category that Republicans frequented, and vice versa. The second category is portal sites — Yahoo, MSN, and AOL — that primarily deliver non-news and non-political content such as email, games, celebrity gossip, and much more. For these sites, the consumption of political news is likely incidental or done as a matter of convenience while one is visiting the portal for other services (e.g., checking one’s emails). This could explain why most of the Democratic and Republican news convergence happens on portal news pages.

Our second study examines how political news consumption responds to the content of the news. If Democrats and Republicans have a strong preference for politically agreeable news content (i.e., news that accords with their political perspective), then they should react positively towards news that has negative political consequences for the opposite party. In particular, we examine the two major “scandals” of the 2016 election: Trump’s Access Hollywood story and Clinton’s Comey letter story. If Democrats react positively to the Access Hollywood story, then they probably have a strong preference for politically agreeable news content (and similarly for Republicans and the Comey letter story).

This is exactly what we find. For the Comet Letter story, Republicans consumed substantially more political news (around two standard deviations more news visits) after the FBI reopened its investigation into Hillary Clinton on Friday, Oct. 28 than expected for a Friday in late October. Similarly, for the Access Hollywood story, Democrats consumed substantially more political news because of the Oct. 7th release of the Access Hollywood tape revealing Trump boasting about making unwanted sexual advances on women. We confirm that these asymmetric effects are not found on days with equivocal political events (such as the presidential debates) or dates with only typical campaign coverage (such as, say, Sep. 19). Thus, our analyses around these major scandals point to Democrats and Republicans having a strong and partisan preference for politically agreeable news.

Taken together, our findings show that media polarization is more prevalent and important for explaining news consumption than previously thought. Most of the media diet overlap we do find is on portal sites that are popular for non-political reasons such as email services rather than politically focused centrist news sources. Meanwhile, Democrats and Republicans appear willing to focus on news sources and events that favor their perspective. Increased demand for segregated news will necessarily weaken demand for “point-counterpoint” journalism and could potentially decrease the market share for practitioners of this genre of news.

This blog piece is based on the article “Partisan Enclaves and Information Bazaars: Mapping Selective Exposure to Online News” by Matthew Tyler, Justin Grimmer, and Shanto Iyengar, forthcoming in the Journal of Politics, April 2022.

The empirical analysis of this study has been successfully replicated by the Journal of Politics. Data replication materials are available at The Journal of Politics Dataverse.

About the Authors

Matthew Tyler- Stanford University

Matthew Tyler- Stanford University

Matthew Tyler is a postdoc at the Democracy and Polarization Lab at Stanford University. His research focuses on causal inference, measuring latent concepts, partisan polarization, and media polarization. You can find further information regarding his research on his website and follow him on Twitter @_mdtyler.

Justin Grimmer- Stanford University

Justin Grimmer is a Professor in Stanford University’s Department of Political Science, Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution, and Co-Director of the Stanford Democracy and Polarization Lab. His primary research interests include Congress, representation, and political methodology.

Shanto Iyengar- Stanford University

Shanto Iyengar is the William Robertson Coe Professor and Professor of Political Science and of Communication at Stanford University. His areas of expertise include the role of mass media in democratic societies, public opinion, and political psychology.